CU Anschutz program helps needy communities get a step up

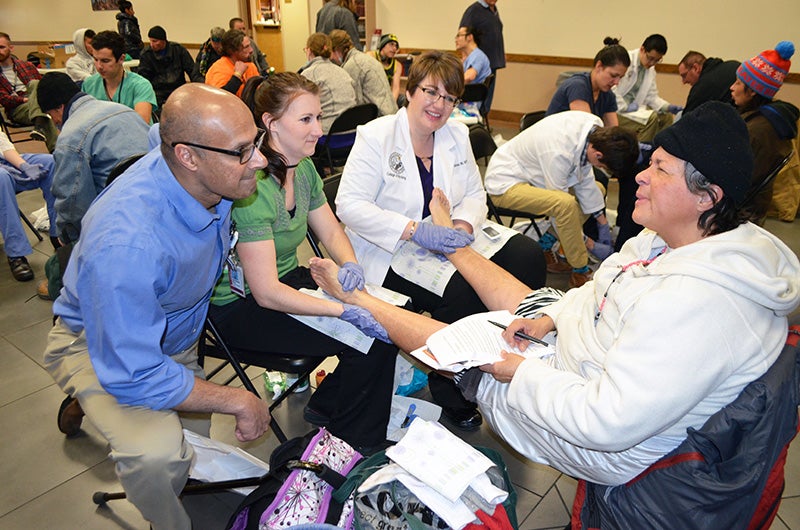

Jamaluddin Moloo, M.D., and student volunteers Dianna Puckett and Aimee Techau speak with Mrs. C, who wants to be sure her saying, "God bless you for life," is included with her photo.

Cathy Beuten

The tall, slender man in a careworn bomber jacket surveyed the CU students and faculty who were cautiously working on the bare feet of seven or so men and women in the room. As he headed out of the Denver Rescue Mission chapel, the man patted Jamaluddin Moloo, M.D., on the shoulder and said quietly, “Thanks, man.”

This small moment of appreciation speaks volumes about how the care of those in need in Denver and beyond is in good hands with the students and faculty in the Urban Underserved Track, a CU Anschutz Medical Campus team committed to helping others get – and stay – on their feet.

On a recent Saturday, Moloo, associate professor of internal medicine and radiology, as well as director of the Urban Underserved Track; Jane Kass-Wolff, associate professor in the College of Nursing; Deb Seymour, associate professor in the Department of Family Medicine, and more than a dozen student and staff volunteers from the track dedicated their skills to treating the feet of the homeless at three local shelters.

By early afternoon, their clients’ feet included the typical spectrum of findings, Moloo said, except for the first patient of the day: a homeless man who had no shoes and had tried wrapping paper towels and plastic bags from 7-Eleven around his feet to protect them from the past week’s icy conditions.

“It didn’t work,” Moloo said. The man appeared to have suffered frostbite and was quickly sent to the emergency room for treatment.

The clinic treated 75 clients over the course of the day staffed by track students and faculty mentors from the School of Medicine (SOM), Nurse Practitioner (N.P.) and Physician’s Assistant (CHA/PA) programs.

“The work of the UUT is important because for much of the clinical time of our students there is little that focuses on the needs of underserved populations such as the homeless, incarcerated, LGBT, etc.,” Kass-Wolff said.

The 7-year-old track, broken into approximately two-year phases of cohorts, comprises blocks that focus on specific patient populations: homeless, LGBTQ, maternal-child, refugees, immigrants, prisoners, substance abuse, mental heath/illness, racism and social justice, as well as hosting a clinic each year to serve those in need of foot care. And while the program has benefited hundreds within these Denver and Aurora communities, the students feel as though they’re the real beneficiaries.

“I come from a social-justice-organizing background in Denver, so I’d been working on issues of underserved populations for a decade before I decided to go back to school,” explained Sarah Bardwell, a SOM student who received her undergraduate degree from CU Denver.

Katie Raskob, a second-year medical student in SOM who graduated from the University of Notre Dame, said service always has been part of her life.

“After my undergraduate degree, I lived in a Vincentian community. It was the embodiment of service all the time,” Raskob said. “That was when I really decided I wanted to work with underserved populations within medicine.”

Shayer Chowdhury earned his undergraduate degree from Johns Hopkins University, doing a lot of work in the Baltimore community.

“What inspired me to join the track is, you start medical school and it’s a drastic transition, you spend hours studying in your textbooks and going to class and, over time, you might forget what really brought you to medicine,” he said.

And that, Moloo said, is what inspired the track to begin with.

“We have fantastic students,” he said. “However, during medical school and residency training and nurse practitioner school and P.A. school, a lot of students lose that idealism that they entered with, so the main purpose of this track is really to help sustain that idealism.”

The track was founded in 2010 by Allegra Melillo, M.D., who wrote the grant and received primary funding from the Colorado Health Foundation, Moloo said. With CHF funding set to expire, the CU SOM, CHA/PA and Nursing schools have committed to help support the track, but more funding sources are needed.

The patients meanwhile sat in chairs with their feet propped on the lap of their caregivers, sharing insights on their toes and their lives’ joys and woes and how the two are intertwined. Just as important to the clients as the foot care: the kindness they were shown and the understanding that these volunteers truly care.

Carolina, aka “Mrs. C.,” wanted to be sure that the saying she tells everyone -- the one she authored -- is included with her photo. “‘God bless you for life.’ It’s what I tell everyone, ‘God bless you for life.’”

She told Moloo, Aimee Techau, a psychiatric mental health nurse practitioner student, and student volunteer Dianna Puckett that when she heard CU students were holding a clinic at the Denver Rescue Mission that day she said, “Oh no, I’m no lab rat.” But, sitting back with one bare foot propped each on the lap of the caregivers, she has changed her mind: She was happy that she came and grateful for CU’s service.

SOM student Billy Tran listens as Seth discusses his recent activities.

Cathy Beuten

Seth warned SOM student Billy Tran that he’s ticklish, promising he’d try to relax so he wouldn’t kick out at him as the student provided the foot care that so many homeless lack and which helps prevent more serious foot infections. “I'm nearly 40,” Thomas said, shaking his head. “And I’m still ticklish.”

Another patient had recently developed sepsis from an infection in his right foot. His only pair of boots didn’t let his feet breathe, he explained, showing off the boots to the two student volunteers working on a foot each.

“I’ve been through a lot of bad things in life, but this was the first time I’ve had anything like that,” he said. The students assured him the infection is healing well and his foot is on the mend.

Donate to the Urban Underserved Track

The emphasis throughout these clinics, Moloo explained, is on the individual.

Jamaluddin Moloo

Diverse areas of medical specialties are important for caring for the urban underserved, and although the track focuses a great deal on primary care, all specialties are welcomed, said Moloo, who was born in Bangladesh before emigrating to Pakistan, Canada and finally to the U.S. He completed his internal medicine training at CU before heading out of state to complete a master’s in public health with a focus on health disparities. He returned to CU in 2008 and along with being director of the Urban Underserved Track, he oversees the refugee health elective for clinical students and works in the fields of Cardiac CT and Nuclear Cardiology.

“We definitely stress the importance of primary care, however our primary criterion for entry into the Urban Underserved Track is a commitment toward serving the underserved,” he said. “Anyone who has worked in any safety-net clinic knows the hardest problem we have isn’t necessarily primary care, it’s getting poorly insured or uninsured patients in to see subspecialists. So regardless of whether you go into orthopedics or dermatology or ophthalmology, all we ask is that when you’re out in practice you leave the door open for those who may be underinsured.”

For instance, second-year SOM students Matt Cataldo, a University of Michigan grad, is drawn toward mental health while Arian Khorshid, a University of Virginia grad, is interested in women’s care and Chowdhury’s focus is on caring for people within the justice system.

The students all had extensive experience volunteering with the underserved before applying to the track and each has a meaningful grasp of the challenges faced by these communities. The track has given them greater opportunities to see these problems from all sides as well as the external obstacles these populations face.

Nathan Fischer, a Colorado State University graduate and second-year SOM student, spent a couple of years working in northern Colorado, primarily with Medicaid patients.

“Working there was pretty eye-opening to me because I saw not only the difference you can make in people’s lives who lack a lot of health care services, I saw a lot of challenges. We were one of the only places around that took Medicaid and I saw the distances people traveled to see us,” Fischer said.

Getting people to where they need to be for assistance is a common issue.

“If you’re uninsured and you have a chronic medical condition that needs treatment, you really don’t have many options for where to go,” Khorshid said. “When the DAWN clinic opened at first, there was debate on whether it would be utilized to the extent that we were envisioning, and right now we barely have enough time to see all the patients that come in.”

The DAWN Clinic (Dedicated to Aurora’s Wellness and Needs) is a partnership between the CU Anschutz Medical Campus and the city of Aurora that opened in 2015. It is a student-staffed free clinic where several Urban Underserved Track students volunteer that offers primary care to uninsured adults in Aurora each Tuesday, and specialty care on other days.

“My primary exposure to the community in Aurora is volunteering at the DAWN clinic,” said second-year SOM student Paul Eigenberger. “So far, the needs that I’ve seen come up there revolve around people not being able to get health insurance and relying on free services, which has a lot of pitfalls. For instance, being able to afford a medication:

Cataldo added, “I had a patient who really needed to get a certain vaccine and they got a prescription to Walgreens to get their vaccine, but they couldn’t because they had a $9 copay, they couldn’t afford the $9 copay.”

Cataldo said he spends most of his time on the Denver Health campus and with the Mental Health Center of Denver.

Fischer agreed. “There ends up being diagnosis and not a lot of follow up, just because of a lack of resources. Health literacy – we’ve had courses we’ve tried to offer that they can’t afford.”

Often, the students said, people can’t take a day off of work to go to the clinic.

“We see some of these patients who come a very long way to get to the clinic to receive health care and expect them to do that on a regular basis. When they’re working several jobs, when they have families to take care of, it is difficult,” Khorshid said.

“There’s a huge housing crisis in Denver and in Aurora and I think even just immediately adjacent to campus there are some lower-income neighborhoods that are being gentrified slightly to make way for the university. It’s displacing people, but it’s a more competitive market.”The track currently has 49 medical students, 12 P.A. students and 22 N.P. students. The curriculum is heavily weighted for the first two years in part because the P.A. and N.P. students don’t have as long an educational road as those in the SOM, Moloo said.

Jane Kass-Wolff

The N.P. students who have gone through the UUT have gone on to find jobs in underserved clinics around the state and nation, she said.

Both students and former students have maintained their investment in the track.

“About a year ago we started a process to look at our curriculum and we essentially brought in the students to help guide the process,” Moloo said. “And so we’ve had a curriculum redevelopment that has been heavily driven by the students themselves. So they, in fact, thought it would be nice to do it as blocks, and that’s how we reconfigured it.”

The students cite the investment their mentors have made in the students and the program.

“We have great faculty for the track,” Chowdhury said. “Dr. Moloo is very experienced in a variety of fields and it’s always amazing to just talk to him because of his wisdom and his experience and his commitment to underserved populations.”

The students cited several faculty and other members who have been spectacular role models in med school, N.P. and P.A. schools. They also appreciated the format, where the focus is on different populations for specific health inequities.

“We’re able to hear as future physicians the personal stories that help influence how I’m personally going to pursue my education or practice the practice of medicine,” Bardwell said.

Another important component is the mentorship the students provide each other, Eigenberger said. “We all have our own unique experiences and backgrounds so when you put all of us together it’s very interesting,” he said.

From left, Matt Cataldo, Katie Raskob, Shayer Chowdhury, Arian Khorshid, Paul Eigenberger, Megan Kalata, Nathan Fischer, Jane Kass-Wolff

Deb Seymour

And so as these outstanding students and faculty mentors in the Urban Underserved Track continue to invest their passion, commitment and care across the Front Range, and with the generosity of departments and other supporters, CU will continue to train a cadre of future health care clinicians with a commitment to serving underserved communities as clearly stated in their mission statement: “Serving those in need, training those who serve.”

“I have valued being a part of this program since I started and hope that it will continue for many more years,” Kass-Wolff said.

- Colorado

- All Four: